Romance and the city

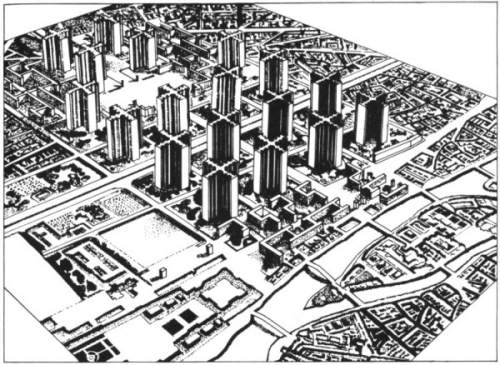

Thank God Corbusier wasn’t allowed to do this:

The larger point Elizabeth Farrelly made (last night at the Albert Hall) was that modernism has meant cities as objects rather than ‘containers for humans’. Modernist cities planned on Corbusian lines plant imposing objects and leave the spaces to fend for themselves, whereas the ideal city - ideal because green, creative, lovely, enchanting - uses the objects to shape the common spaces. The buildings are simply the wallpaper of streets and squares as inviting rooms for people to live in, not look at. I like this notion, but don’t see that it has to be quite as gendered as Farrelly makes it: towering as masculine, textured as feminine. Whatever might be argued about modernism and masculinity, you don’t have to see modernism’s remedies as feminine to think they’d make better cities. More interesting to me was the tension between planned spaces as livable and organic spaces as lovable. Planned space might tick all the boxes, but the plan’s no good if people don’t flow wantonly and naturally in and out of the space. The answer seems to be about the play of both in history: what Farrelly called a ‘dance’ of evolution and intervention across time. Maybe that’s why Canberra feels overplanned and undercooked. The dance is only just getting started. Maybe in two or three or five hundred years, Canberra will be closer to the enchanting ideal.